In an effort to develop their critical thinking skills, the students staged a mock trial, demonstrating the process of reflection and repentance outlined in Jewish law. The process included analyzing the laws, reflecting on their actions, implementing the steps of repentance, evaluating how to prove each step and creating admissible evidence.

Entry Narrative

Introduction:

Student self-reflection is increasingly recognized as a critical skill for effective learning. When students consistently participate in a process of evaluating what they learned, how they learned, and whether they still have more to learn in order to achieve a goal, they become expert learners who are engaged, purposeful, and motivated. In addition to the educational benefits, student self-reflection has the potential to be utilized as a tool for improved character development. In Judaism, this ideal is built into the calendar each year beginning in the month of Elul through Rosh Hashanah and culminating in Yom Kippur. During this time period, we are tasked with reflecting on our actions through the teshuvah (repentance) process. This gives us the opportunity to pause and critically analyze what we have done and decide if there is anything we did wrong or could have done better. Unfortunately, students are often taught the traditional steps of this process, memorize them for an assessment, but fail to internalize the true message of repentance by applying the process to themselves.

In order to empower my students with the skills, knowledge and appreciation of self-reflection, I designed a curriculum unit that required them to analyze the laws of teshuvah and apply the information to their lives. The students identified areas where they could have done better, produced evidence to prove they had completed each step of repentance, and participated in a mock trial before a judge who assessed whether they had successfully implemented the process. This created a way for the students to apply a longstanding tradition to their modern lives. Each part of the assignment necessitated the critical thinking skills of analysis, evaluation and re-evaluation. This allowed many of the students to see themselves as more capable learners than they had previously thought, in addition to the contribution it made to their character development and religious growth.

I designed this project utilizing two current, research-based frameworks for teaching: Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Project Based Learning (PBL). UDL addresses the needs of diverse learners by proactively incorporating options into the curriculum so that all students can access learning in the classroom. It is grounded in the theme of “universal design,” which originated in the field of architecture – rather than retrofitting supports onto a building after it is finished, architects incorporate those features into the design itself. When applied to education, universal design uses research on how the brain learns to help teachers plan lessons that are flexible when it comes to how students engage in learning, receive information, and demonstrate understanding. PBL is an approach to learning where students actively engage with a meaningful topic over an extended period of time, analyze information, and acquire deep understanding. It is not just about producing a product (project), but rather about the growth that students experience through the process of exploring and applying ideas. This project fuses UDL and PBL. It is designed so that diverse learners can access it differently- some with more support, others with less. In that way, it addresses the needs of students who require more scaffolding to learn, as well as those who need more opportunities to guide their own learning. This project also involves students actively constructing and applying knowledge in a way that is directly applicable to their lives as members of the Jewish people.

Overview of Unit

This unit is designed to be appropriate for grade levels 6-10. Students in grades 8-10 will be able to do the project more independently, while students in grades 6-7 will need more scaffolding and assistance throughout the unit. The unit will take several weeks to complete. Younger grades will need more time than older grades due to the assistance needed.

The students will engage in learning that exercises three levels of the Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy: analysis, evaluation, and creation.

The students will:

- Learn the halachot (laws) of teshuvah.

- Analyze the laws by breaking them down and summarizing them to form a big picture of the “how to” of teshuvah.

- Implement all of the steps and aspects of teshuvah prescribed by the Rambam.

- Develop a defense for a classroom mock trial in which each student must prove to the court that he or she has done a proper teshuvah.

To prepare for their court appearances and defenses, students will:

- Analyze and evaluate which forms of evidence will work for which aspect of teshuvah. There will be a great deal of trial and error, where re-evaluations will be necessary.

- Develop, design, and create different pieces of evidence for each aspect of teshuvah.

- Present their evidence in court and undergo a cross examination by a prosecuting attorney (teacher).

Development/Procedures:

Begin the unit with an introduction to teshuvah. This could be done by asking the students what they already know about teshuvah, and telling them a short story demonstrating the power of reflection.

Present students with the Rambam Source Sheet to engage them in primary source study. The studying of these sources can be done independently, with a study partner, or as a whole class.

- The students will learn through teacher-selected halachot of the Rambam in the Yad Hachazakah on the laws of teshuvah.

- After learning each halachah, the students will summarize in bullet form what each halachah is telling us. This can be completed in the left margin of the source sheet.

For the rest of the project, students can either work independently, or they can work with a partner and assist each other.

After learning the relevant Jewish laws, students will now complete the Project Organizer to help them prepare for the “legal proceedings” in which they will participate.

- The students will organize the laws that they learned by filling in the their project organizers, listing:

- The 4 basic steps of teshuvah

- Admitting guilt

- Feeling sorry

- Accepting the responsibility to ensure that it will not happen again, as much as possible (and creating a plan to that end)

- Asking the person for forgiveness (if the sin was against someone else)

- Additional actions which will rip the decree up completely

- Prayer

- Charity

- Separating yourself from sins in general (making fences for yourself)

- Changing your reputation

- Being humble

- The two actions that if done, G-d will not help you do teshuvah

- One who causes people to sin

- One who does not stop someone from sinning

- The 4 basic steps of teshuvah

- Students will then need to choose a sin that they actually did.

- They will then need to plan out how they are going to do each step of teshuvah. They must keep in mind the necessity to prove to the judge that they did that step sincerely using a different type of evidence for each aspect of teshuvah. They will also need to use all listed types of evidence (on page 2 of Project Organizer) one time. The purpose of matching one form of evidence to each step of the teshuvah process, as opposed to allowing students to repeat forms of evidence, is to deepen the level of analytical thinking. Students will need to analyze and evaluate the goodness-of-fit between their choice of evidence and each step of teshuvah. This allows for a process of re-evaluation, trial and error, and problem solving, which are critical in the development of expert learners.

- Starting with page 3 of the project organizer, the students will fill in the evidence they plan to use, a description of the evidence, and the location of that evidence (Google Drive, physical folder etc.). Every student will create a Google Drive Folder that will contain all of their high tech evidences, and they will also have a physical folder that will contain any hard copy papers that they will need.

- Note: All pieces of evidence will need to be of real teshuvah; not a re-enactment. This makes the experience real, it also makes it more challenging to figure out how to utilize each type of evidence. The one exception is the “forensic animation,” which is a re-enactment of what was done, using an app to make an animated video or a comic.

- The students will need to go through each aspect of teshuvah and design, develop and create the appropriate evidence.

- Instructions for the forensic animation:

- Have the students create a re-enactment of the aspect of teshuvah that they completed, using either:

- “Plotagon,” a great app available on an iPad, etc. This is a very easy program, which can be used to make animated videos. The students can even make an avatar of themselves and include that character in their videos.

- Make a comic using one of the many free online websites. Here is a list of a few options:

- Have the students create a re-enactment of the aspect of teshuvah that they completed, using either:

- Instructions for the forensic animation:

- In Hilchot Teshuvah, the Rambam explains the idea of free will. He explains how we are the ones making our own choices, even though G-d knows what will happen in the future (i.e. G-d is outside of time, so to Him, everything is happening at once, even though from our perspective, we are moving forward through time as we know it – Tiferet Yisorel’s understanding of the Rambam). The students will then have to create a 3-D model representing the concept that we have free choice even though G-d knows what is going to happen in the future. This is to show that they understand that because they have free will, they are the responsible party. The Rambam puts this concept in Hilchot Teshuvah for this very reason. We need to understand that we are not just “robots” pre-programmed to carry out different actions; instead, we are the ones making our own decisions and therefore we are responsible for our choices. Only once we internalize this, can our teshuvah be sincere.

- This part of the project is deliberately left open-ended. The model can vary both in concept and in the final product, dependent on the students’ abilities.

Presentation – The Mock Trial

- The students will have to present their evidence to a judge (someone intimidating, such as a principal or head of school).

- The prosecuting attorney (teacher) will cross examine the students. The teacher should ask follow up questions to ensure that the student understands each aspect of teshuvah and that the student completed each step with sincerity.

Grading

See the project rubric for grading. There are 2 rubrics. One of them is the rubric for the entire project. The “Rubric of Presentation” is the rubric that the judge fills out as the verdict for the case. The judge’s rubric is then counted as part of the whole grade for the entire project.

Impact on Students

I think there was a great shift in my students’ mindset. Many of them came into the unit with a more fixed mindset. When I first introduced this unit to my students, some were overwhelmed. Comments like, “We will never be able to do all of that,” or “But I am not good at…” were common. As they started to work through the unit, you were able to see on their faces their confidence growing stronger and stronger. Comments started to sound more like, “Rabbi Perles, can you help me with this?” and “OK, I did that, now what do I do next?” Towards the end of the unit, students were so engaged and were truly taking ownership of their own progress. The classroom was then filled with comments such as, “Rabbi Perles, take a look at this!” and “Wow, that looks great!” Their mindsets had clearly shifted from a fixed mindset to a growth mindset. Before the trial, the students were understandably nervous, but after it was done, they all felt extremely proud of themselves. I was shocked to see how sincere some students were in their teshuvah. One student even started crying in the video that he made of himself, expressing how sorry he was for disrespecting his mother, which he later showed to her. Another student at the mock trial expressed how badly she felt for very often forgetting to say a berachah, a blessing, before eating. She expressed such a desire for growth. She opened up about how it felt to go from a public school to a Jewish day school. She described her feelings and laid out plans to further her growth. I was personally so inspired that I started to take my own berachot more seriously. The students saw what they were truly capable of, both in terms of their academic abilities as well as their spiritual connection to Judaism, G-d, and their own self.

Areas for Improvement

Based on the impact this project had on the students, I think that the unit was a tremendous success, but there were some areas that could use some development. Most students were able to complete all of the parts of the project, however there were a few students who did not have enough time to do the 3D model. These students were working hard the entire time; however, they sometimes got carried away with small details, which made each step take a great deal of time. The line between producing quality work versus getting caught up in the details is a very tough balance. You want the students to feel good about their work, to take pride in it, but at the same time, you also want to teach them the skills of keeping to a deadline and knowing when to make peace with what is a great product, even though it may not be perfect. In the future, when I do this unit, I may give a mini-lesson on this balance, to proactively explain to the students the challenge and hopefully give them some strategies to be successful.

Another area for development is the 3D model, which represents the concept that we have free choice even though G-d knows what is going to happen in the future. I specifically left that part of the project open-ended so that the model could vary both in concept and in the final product, dependent on the students’ abilities. However, in the future, I would create more structure to the expectations. The students who did do the model all did a phenomenal job, but they did need to ask many questions, and they also needed a great deal of scaffolding for them to be successful. I think that more structured expectations, which are clearly spelled out, will allow the students to be more independent in this part of the project.

Examples of Student Work

Here are some examples of diagrams that students created as pieces of evidence:

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1VC1l0hwWXDDO47upcmhbsoSGxbk1jEv6mZRnORlwnFs/edit#slide=id.p This is a diagram proving to the court that the student does not get other people to do sins. On the contrary, she helps people do good deeds.

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1u9MqDo_mT01ZtNT2FiBrQVnOUX9Kbrm-F2rG-DVxkRo/edit#slide=id.g3f389e2785_0_0 This is a diagram depicting the students’ process of feeling sorry.

The following are some examples of animated videos, which the students created using Plotagon for their forensic animation.

https://drive.google.com/open?id=18AZoxaYW86-2bs1fcoroqObkeOG11B1y This was evidence brought by the student to show that he is humble. It is a re-enactment of the student responding without arrogance when confronted by a friend who was showing off.

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1tBdyqOIMC5zVw0JNrxpgAln2kursVIk7 This was evidence brought by the student proving that she set up barriers from speaking gossip. Whenever she hears someone speaking gossip, she physically leaves the conversation.

Below are examples of student-created comic strips as their forensic animation:

http://tinyimg.io/i/WeS2u0r.jpeg This is a sticky note that a student created for his material evidence showing that he came up with a plan to try his hardest to not do the sin again. His sin was eating before feeding his dog. He put this sticky note on his fridge so every time he would go get food, he would first be reminded to feed his dog first.

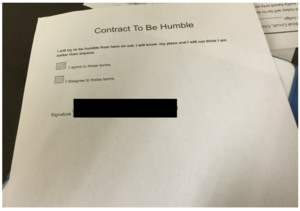

This is a contract a student made with herself committing to be humble, and defining what that means:

Here are 2 examples of the models that the students created to depict the idea that even though G-d knows what is going to happen, we still have free choice. This is based on the idea (explained by the Tiferet Yisroel) that G-d is outside of time, while we are within time.

http://tinyimg.io/i/Mh0sdbj.JPG This model has two components. The first is a 2D strip showing our perspective. We go through life making choices. We can make the right or wrong choice. We are going through it sequentially. The other component is G-d’s perspective. It is a mobius strip in which the person’s pre-choice and post choice are on opposite sides of the page, but due to the flow of the mobius strip it appears all on one side. This symbolizes the fact that to G-d, it is all happening at once.

http://tinyimg.io/i/QnuEeVn.jpeg This model shows a chutes and ladder game with 2 decks of cards. One deck is the person’s and the other is G-d’s so to speak. The person’s deck is all scattered around and the person chooses if he/she wants to do a right choice card (with a specific choice on it), or a wrong choice card (with a specific choice on it). If they choose a right choice they go up a ladder, and if they choose a wrong choice they go down a slide. G-d has the same deck, but all of the cards are stacked in one pile, to show that from His perspective it all is happening at once, and in the order that the person will choose it in.

Here are videos of parts of some cross examinations:

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1uHSSSpE4AC65FYjiNBggFRxUB9jManyY

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1iDzU9mleTwJicz8uBBmM0kNw-NF_J4XP

Entrant Bio(s)

Rabbi Eli Perles is a special educator and Judaic studies curriculum specialist at Sulam, a special education program in the Greater Washington, D.C. area for students with diverse learning needs. He received a Master of Science degree in Special Education from Johns Hopkins University and rabbinic ordination from Ner Israel Rabbinical College. In his years at Sulam, Rabbi Perles has focused on integrating research-based best practices into his classroom teaching, curriculum development and mentoring of novice teachers. Most recently, he participated in a Professional Learning Community, where he trained educators in implementing Universal Design for Learning in a Judaic studies curriculum.

This entry has been tagged with the following terms: