Middle school students learn Rabbinic texts about prayer’s structure, purpose, and origins, while simultaneously evaluating their own relationship with Tefillah in a reflection journal. The entire unit builds to a trial created by the students and presided over by a panel of local community rabbis, pitting Keva Tefillah against Kavanah Tefillah.

Entry Narrative

Jews have always had complex relationships with Tefillah, and as emerging adults, middle schoolers often struggle to find their own relationship with Tefillah. The project, Keva Vs Kavanah: The Trial of the Millennium served as an introductory unit to Gemara for seventh-grade students, and encouraged them to synthesize their learning by developing their own relationship to Tefillah as they encountered diverse models of prayer within the Jewish tradition.

The ideas of Keva and Kavanah have been held in tension by generations of rabbis, and throughout this project students were encouraged to join the rabbis’ conversation by personally considering the role that these concepts have in their individual experiences of Tefillah.

Keva Tefillah is the sort of prayer our students most encounter in their schools and synagogues. It has a set liturgy, and is completed in a predetermined time, and often in a specific place. Keva Tefillah generally involves reciting words out of a siddur.

Kavanah literally means “intention” or “sincere feeling,” and a Tefillah focused on Kavanah is less centered around specified words, times, or settings. A Kavanah-centered Tefillah is one in which the pray-er communicates with God spontaneously, independently, without using pre-set language.

While Keva and Kavanah were set up in opposition to one another during aspects of this project, the idea that the ideal prayer contains elements of both Keva and Kavanah was mentioned throughout the learning. Within the learning, students analyzed both types of Tefillah and argued their particular merits.

This project took place in a 7th grade Rabbinics class at a community day school. It had several explicit learning objectives:

- Students would be introduced to learning Gemara, and gain skills in reading and understanding a new form of Jewish literature

- Students would be able to identify how modern Jewish practices developed from ancient texts

- Students would be able to analyze Rabbinic texts to better understand the origin of Keva and Kavanah

- Students would explore their own relationship with Tefillah, and record their ongoing thoughts and feelings in a personal journal

- Students would prepare for, create, and participate in a trial where they argue for either Keva Tefillah or Kavanah Tefillah. The trial would be presided over by a panel of local community rabbis

Component One: Learning Biblical and Rabbinic Texts

To prepare for this trial, students began by learning foundational texts related to Tefillah as their first introduction to Gemara. Students initially learned Mishnah Brachot 4:1 (the timing of daily prayers), followed by a selection of Gemara, Brachot 26b, that was based on this text. I prepared worksheets for the learning of these texts, with different amounts of English to support to the diverse learners in the class. After translating these texts, students demonstrated their comprehension in an oral exam, in which they had to accurately read aloud, phrase, translate, and explain a traditional page of Talmud.

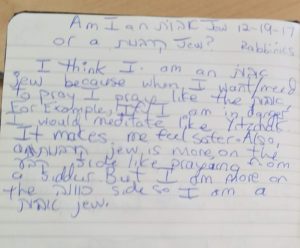

The Gemara text teaches how the daily prayers were instituted, either by our forefathers (“Avot”) after specific moments in their lives, or after the daily sacrifices (“Korbanot”) which were commanded in the Torah. Students understood that the “Avot” interpretation aligns with the idea of Kavanah Tefillah, in which prayers are said spontaneously in moments of fear, praise, or transition. The “Korbanot” interpretation aligns with the idea of Keva Tefillah, which are said at specific, pre-determined times. By looking at the Torah texts that the Rabbinic texts were based on, students were able to trace how the rabbis of the Talmud developed and based their rulings on older texts. This learning built to the central question students were asked to personally reflect on: “Am I an Avot Jew, or a Korbanot Jew?”

Students also examined a second selection of Gemara, Brachot 31a, learning and translating as a class. In order to understand this text, they first studied the beginning of Shmuel Aleph, where Hannah prays for a child. They then traced how the sugya (selection of Talmud) develops this moment of spontaneous prayer (Kavanah), into the foundation of many set laws (Keva) in Jewish prayer today.

Component Two: Exploring a Personal Relationship with Tefillah

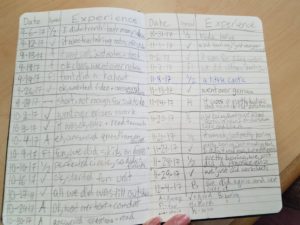

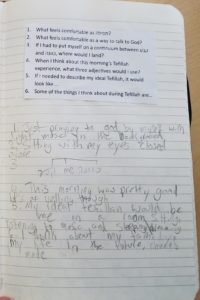

At the beginning of the school year, I distributed to each student a personal journal. This journal was intended to feel “grown up,” with a hard cover, bookmark, pocket for notes, and with an elastic band closure. The journals were intended to encourage students to pause at the end of each class to consider their own state of mind, review the day’s learning, and make connections between their lives and the text in a short written reflection. This daily opportunity to synthesize learning helped the students retain information, engage with the material, and facilitated a classroom culture of individual reflection.

At the end of each class, students were asked to write a reflection on the previous class. At the beginning of the school year, these were often short summaries of the class itself. Some students struggled with this more open-ended format, and as the year progressed, I changed the prompt to the following format: Today class was ________ and personally, I was ________. One thing I learned today was ________. I am grateful for ________. This change helped the students more clearly reflect on their experience of class and synthesize the information they learned that day.

About once a week, students also thoughtfully responded to writing prompts in their journals. I wrote prompts which asked the students to reflect on their own prayer experience. Some questions asked students to compare their own thoughts and feelings to the texts we had learned. Other questions asked the students to reflect on their own feelings after a specific prayer service in school. Additional writing prompts encouraged students to reflect on different types of prayers they had experienced. The reflections also provided multiple opportunities for each student to reconsider and change their stance depending on their state of mind. Moreover, students were able to monitor or recognize trends in their own thinking about this topic.

Toward the end of the unit, students also used their journal to analyze and respond to the central question, “Am I an Avot Jew or a Korbanot Jew?” Students explored which type of Tefillah they most personally relate to, Keva Tefillah (Korbanot) or Kavanah Tefillah (Avot). By responding to this question, students were able to synthesize much of their learning from the past few weeks. Students compared and contrasted the different elements of prayer, and through individual reflection, determined what their own personal Tefillah preferences were.

Album of Students Journals – Including Daily Reflections, Weekly Writing Prompts, and Avot/Korbanot Answers

Component Three: The Trial of the Millennium

I motivated students from the beginning of the unit by explaining that they would be creating and taking part in a trial, where they would be required to defend Keva Tefillah or Kavanah Tefillah. Students were told that the trial would be based on their analysis of the texts and their personal reflections. To help raise the stakes, the trial’s jury would be composed of local rabbis from the community, including the family rabbis of many of the students.

An exciting component of completing each text was when students completed a Witness Sheet that summarized key information about the characters from the sources and evaluated which side they would be a good witness for, and why. Additionally, if possible, the students would also consider the opposing side and record on their witness sheet why this individual character could also serve as a witness for the opposition. Students collected these witness sheets over the course of the unit.

Students then spent almost two weeks in class preparing for the trial. They watched selected movie clips which highlighted key elements of a trial: Depositions, Opening Statements, Witness Testimonies, Cross Examinations, and Closing Statements. The students in each class were divided into two parts, based on their answers in their journals to which side they more closely related to, Keva or Kavanah.

During this time, the students worked in small groups composing questions and answers for the witnesses, and these witness depositions later became the scripts for the trial. Students needed to evaluate what an honest answer from each potential witness would sound like, and determine if that witness would be best for their side, or for the opposition. Writing these depositions integrated the learned texts into a modern court scenario, encouraging students to support their side with textual evidence.

By having each side also cross-examine witnesses, the students needed to critique the opposing side’s argument with additional evidence, demonstrating an ability to see multiple perspectives within a single text. Students also collaborated as a team to write the opening and closing statements for their side’s lawyer, synthesizing all the material they had learned into a persuasive speech for the trial. Finally, they selected who would have which roles during the actual presentation of the trial. There was one run-through of the trial in class, the day before the final presentation.

The trial was performed twice, once by the morning class and once by the afternoon class. For each trial, three or four community rabbis came in to serve as the jury. The rabbis came from across the denominational spectrum, but all served communities within the school’s catchment area. Bringing in rabbis from outside of the school helped lend gravitas to the learning and encouraged the students to work hard on their preparation and presentation. The rabbis had been provided the texts ahead of time, but were asked to make their judgments based on the students’ arguments in the trial.

The rabbis listened carefully and took notes. Following the trial, while the rabbis deliberated, the students wrote in their journals. The students reflected on their experience in the trial, and considered whether or not they still felt as they had at the beginning of the trial, and at the beginning of the unit. Before the final verdict was revealed, the students analyzed in writing their individual development as learners and “pray-ers” throughout the unit.

When the rabbis revealed to the students which side won, they also included in their final statement some of their own personal thoughts, feelings, and struggles with both Keva and Kavanah Tefillah. The personal statements from the community rabbis modeled for the students an authentic, personal, ongoing engagement from leaders whom the students greatly respect. Their rabbis’ personal “statements” also encouraged and gave permission for the students to see that the tension between elements of Tefillah continue, even among professional pray-ers.

Album of Trial – Photographs of students and rabbis from both trials (morning class and afternoon class)

Student Feedback

The student feedback for this unit was overwhelmingly positive. Following the trial, the students were asked to complete a short survey. Two questions and a representative selection of the student responses are below.

How well do you think you did on the preparation of the trial material?

- We were really well prepared, we all knew what was expected of us.

- I think we did a lot of preparation and it really payed [sic] off.

- I think our group did very well, and I participated a lot in the preparation.

- I think that we were well prepared, and that our material was ready and thoughtful.

Do you think the trial was a good reflection of the learning we did?

- Yeah, because it had a lot of the text that we learned and showed how much we had thought about Keva and Kavanah.

- Yes I do think that the trial was a good reflection of what we did instead of just having like a test or something.

- Yes because we got to put our learning to use in something that was fun.

- Very much yes, I think it was a great way to incorporate all of our learning into a fun project.

- Yes because it was a good fun way to discuss and present our work.

Final Thoughts

This project was a powerful and creative platform for middle school students to connect with the many ideas within traditional Jewish Tefillah, while also encountering new Rabbinic texts for the first time. Students across skill levels were required to use their analytical skills to consider other perspectives, as well as their creative capacity to synthesize the content through a new lens. Because the students knew about the trial from the very beginning, they were engaged throughout the learning process, and had their sights set on a larger goal.

The reflection journals offered students the opportunity on a regular basis to sit back and think about themselves as students and pray-ers, encouraging them to be reflective in their daily lives as well as their prayer lives. In preparing for the trial, students developed convincing arguments by integrating learned material into their trial scripts thereby justifying and supporting their perspective. Finally, the idea that the ultimate decision of the trial rested upon the rabbis from the community made the learning feel real and genuine to the students, taking it outside the four walls of the classroom and into the greater community.

Entrant Bio(s)

Sarah Zollman is in her eleventh year as a middle school Judaic Studies teacher at Carmel Academy. She has a BA in Jewish Studies from the University of Florida and is a graduate of the Pardes Educators Program, where she earned a certificate of Advanced Jewish Studies alongside a Masters in Jewish Education from the Shoolman Graduate School of Jewish Education at Hebrew College.

This entry has been tagged with the following terms: